"Voting-Eligible Population" Helps Explain Trump's Dominance, and Vulnerability

An overlooked framework for understanding the 2024 election

I hope the half of this essay about Donald Trump’s dominance of the Republican Party ages poorly, and there is a chance it might, as he embraces tariffs that are already cratering the stock market and appear likely to push the U.S. economy into recession.

Regardless, I wish to offer a datapoint that has helped me understand why, scared as they might be of their own voters, elected Republicans struggle even now to diverge from Trump’s least popular and most self-destructive actions. That key metric is “voting-eligible population,” brought to my attention by a random person on Bluesky a few days after the election. I have struggled to find any discussion of it online.

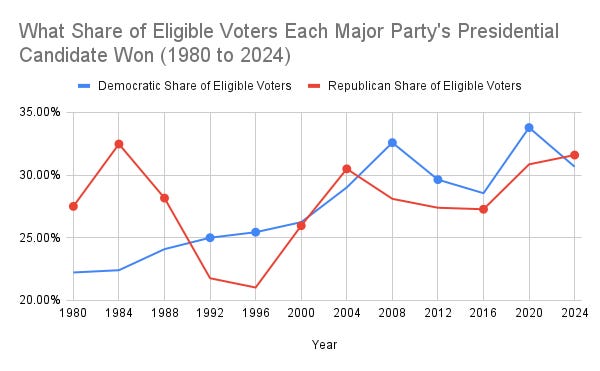

If we analyze presidential elections in terms of eligible voters, we see two significant trends. Trump won larger shares of eligible voters in 2024 and 2020 than he had four years prior. And Democrats suffered a historic regression in 2024 — but also in 2012.

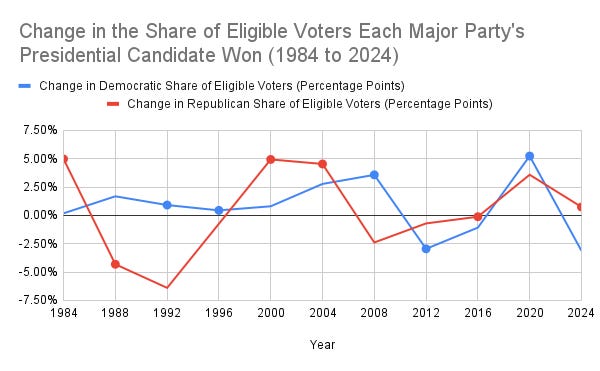

The first chart shows the percentages of eligible voters that the Democratic and Republican nominees won in presidential elections from 1980 to 2024. For example, in 1980, the Republican won 27.50% of eligible voters, while the Democrat won 22.23%. The winning party for each election is marked by a dot. The second chart, below, shows the difference in percentage points between elections; Biden won about five percentage points more of the eligible voter base in 2020 than Hilary Clinton had in 2016, a large increase. Bush Jr. saw similar improvements in both of his elections.

After Ronald Reagan’s coattails ran out in 1992, Republicans struggled for about a decade and a half to identify or even articulate a path to a national popular majority.

During that span they won the popular vote only once, in 2004, when George W. Bush benefitted from the rally-around-the-flag effect of 9/11 and the Iraq War, which had not yet fully unraveled, and which his opponent John Kerry voted for, limiting his ability to differentiate himself. The prime importance of national security in that election generally favored the incumbent — “don’t change horses in midstream.”

The popular vote was extremely close in 2000, but that is a testament to Bill Clinton’s popularity. A two-term president’s party generally loses the next election. Bush Sr.’s win in 1988 is a testament to the revolutionary success of Ronald Reagan’s presidency. So is the fact that Republicans were otherwise unable to replicate it. On a related note, Republican Senator Ben Sasse of Nebraska implied to me ten years ago that Trump would win, because he was a historian by training (Sasse said that during our only conversation; I was a reporter and it was off the record, but he later left politics).

Trump won extremely narrowly in 2016 as the ultimate political outsider, starting with the fact that he was not really a Republican and did not care about the party’s established positions. Then something odd and easy to miss happened. Even after he thoroughly mishandled COVID-19 and distanced himself from the miracle of Operation Warp Speed, Trump won a higher share of eligible voters in 2020 than he had four years prior. And even after January 6th, he accumulated an even larger base of support, actually winning the popular vote in 2024, though not a majority.

This is a basic explanation for the mind-bending staying power of Trump and MAGA populism. He helped a losing party win the White House. And he built a new coalition.

Democrats’ recent success appears to be as tenuous as Trump’s victories. They won a smaller share of eligible voters than four years prior in 2024, 2016, and 2012, when President Obama defeated an opponent who lacked all of the charisma he had. Before 2012, Democrats had steadily grown their share of eligible voters, even when they lost.

The steep drop in Obama’s vote share from 2008 to 2012 was perhaps a warning sign that his supposedly transformational platform was not very popular, his coalition not built to last. Indeed, Trump’s 2016 victory is easiest to understand as a populist repudiation of Obama’s legacy and the highly educated voters his party still caters to.

We can tell ourselves many different stories about politics. Here is what makes the most sense as I look at these numbers and the past two decades’ electoral oscillations.

Obama won a quasi-landslide in 2008 on promises of hope and change amid the Great Recession. That hope dimmed as the job market recovered slowly, but his opponent was a private equity executive and the son of a governor — an archetypical insider and rich guy whose robotic personal affect doomed him. Romney tried to empathize with a voter at the Iowa State Fair by lecturing him that, “Corporations are people, my friend.” I loved Mitt Romney when I was a teenage neocon and I love him now, but in between I was a Ron Paul supporter who saw him as the establishment personified. (Imagine Romney winning in 2012 and 2016, then PowerPointing COVID into oblivion.)

Trump capitalized on the lack of change working-class people felt by the end of Obama’s presidency. After Wall Street got bailed out and the China shock leveled the rust belt, they saw that people like Obama — educated, cosmopolitan, bohemian — were doing well, while many of them were stuck in dead-end jobs or decaying towns.

2020 was a fluke that delivered Biden a mandate for stability, but instead of normalcy voters got high inflation. Voters picked an ill-tempered man who had cultivated an avuncular image late in life. Biden said he would be a bridge to the next generation but turned out to be too frail to run again and too stubborn to step aside, even though something like 80% of the public had concerns about his age. By the time he bowed out, it was too late. Biden’s uncharismatic vice president actually did remarkably well, winning the largest vote share of any Democrat other than himself and Obama ‘08. Regular people felt stuck and saw they were being lied to. The emperor had no clothes and the “Inflation Reduction Act” was actually a massive green energy spending spree (which I can grasp and you might like, but it sent the wrong message to swing voters).

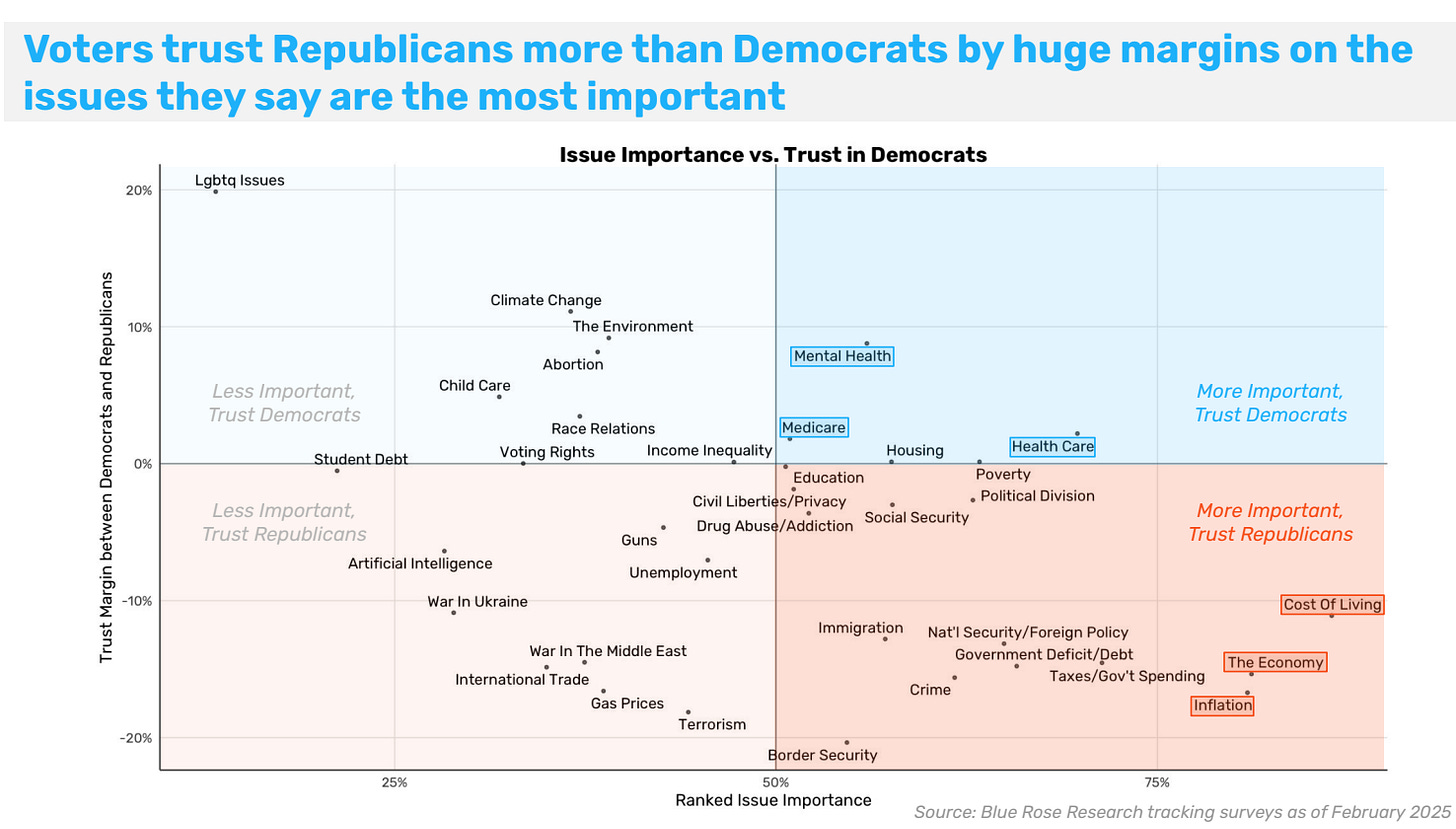

Trump won in 2024 by hammering the most salient issues: inflation and the economy. What about cost of living and thus housing? Well, what do the most expensive places in America have in common politically? Progressive supermajorities. As Democratic elections data analyst David Shor explains, Dems fumbled the issues voters care about:

I do not like populism because it appeals to people’s anger and ignorance and embodies a zero or negative-sum worldview, so I do not want Democrats to try to beat Trump and JD Vance at that game. But I also genuinely do not think they would be able to. A dear friend tells the story of sitting in a cafe in Greenwich Village, after she had transferred to Columbia University, and hearing some guy pontificate about “the revolution.” She stopped him and said, “You know that if the revolution comes, we would be some of the first people to be killed, right?” My friend is far to my left yet we agree that Democrats should be working to make people’s lives better, not just talking big.

The silver lining of Trump’s second election is a clear sense of what voters prioritize — the problems the American people want their leaders to fix. Trump’s love of tariffs might finally destroy his political brand. Either way, the recipe for something better that will appeal to far more voters is surprisingly clear and straightforward. Whoever builds that coalition has a chance to grab a huge slice of the electoral pie.

Thanks to my 1,035 subscribers, especially my 16 paid subscribers. If you enjoy this blog or want to work together please contact lucagattonicelli@substack.com. I founded the grassroots pro-housing organization YIMBYs of Northern Virginia and live in Alexandria near DC.

Despite the Republican concern trolling, the Republicans never really offered any solutions for consumers facing higher prices, and advocated for higher costs for certain populations, such as student loan borrowers. I do not recall any republican expressing any way to actually help consumers, yet they won on this messaging. It also seems that Trump has cultivated a cult of personality, with die hard supporters following trump on every issue. Yet, no other Republican politician seems to be able to reproduce Trump's success. Ron DeSantis took up many of Trump's positions and promised to go after LGBT individuals, yet he fizzled out in the primary.