Why Cars In The U.S. Are Not Smaller

Thinking through potential direct alternatives

Urbanists including myself dislike that cars take up so much space and that their heavy weight and high speed make them dangerous to people anywhere nearby: walking on the sidewalk, in another car, or even inside a building at ground level. Yet it is hard to find any new car, never mind a good one, smaller than a roughly 3,000-pound Toyota Corolla in the U.S. The ~2,600-pound Nissan Versa is the only subcompact non-premium sedan on sale in America today, with the discontinuation of the sedan and hatch versions of the Mitsubishi Mirage, which barely weighed 2,000 pounds. That evocative name was wasted on the cheapest, worst new car you could buy here. The Versa I drove as a loaner was a piece of junk. Heavy rain sounded like it would damage the roof, and braking downhill in wet conditions was nerve-wracking.

Yet even Japanese Kei trucks and cars that have become a charming fad in the U.S. weigh about 1,500 pounds. The original two-passenger Smart car weighed about 1,600 pounds. So why are cars so heavy? And why do most of them end up being so big?

My answer is a combination of physics and economics. I will assume consumers have some desire to not be killed or injured in a crash and to save money on fuel, but I will set aside regulations, including fuel economy standards that let multi-ton pickup trucks off the hook. A vehicle able to convey at least two adults in reasonable comfort and safety has certain basic engineering requirements that pile on the pounds. And car buyers make decisions on a margin that pushes them toward four wheels, four passengers, and some cargo space, even a single person living alone who only needs a car to commute. This is really just my take as a car enthusiast, but I do feel confident in my reasoning (and I hope it will help urbanists understand cars a bit better).

The two car alternatives that come to mind are a golf cart and something like the Elio pictured above: A three-wheeled commuting vehicle which has most of the comfort and safety of a traditional car, but is much more efficient and affordable. Elio targeted a 1,350-pound curb weight for its original internal-combustion three-wheeler. The company may or may not be a scam, but the concept still is compelling, so we will give it a fair shake. We should start with the cheapest option: A golf cart.

This is a Club Car Onward 4-passenger model. As shown with a gasoline engine, side mirrors, a roof, and a DOT-approved windshield it costs $13,817 before taxes. It weighs about 800 pounds. Finally, a light vehicle, right? Why should a car weigh an order of magnitude more than one adult? It is easy to imagine four 200-pound adults comfortably tooling around on a cart that weighs about as much as they do.

Yet the Onward has some glaring limitations. Even a cart with seatbelts and doors (and AC) would not offer any crash protection from other cars. The lowly Mitsubishi Mirage or a little Japanese Kei truck would devastate the cart in a crash. And extra features like doors, which are hardly frivolous, would add weight and cost.

So for primary transportation, we have probably graduated to something like a Japanese Kei car. These little marvels receive special tax treatment for having a small engine size and footprint, though Wiki says the Japanese government greatly curbed their tax advantages in 2014. The Honda N-Box is a popular and well-regarded model. Aesthetics are subjective and I am easy to please, but I think it looks fantastic.

I do need to mention that a big reason Americans prefer larger cars is that we can afford them. We easily forget how much wealthier we are than most of the global population. Small cars are popular in developing markets with low median incomes. However, I would attribute Kei cars to Japan’s need to use scarce land efficiently.

The N-Box weighs in the realm of 2,000 to 2,300 pounds. It is a respectable, up to date car, just tiny: HVAC, seatbelts, airbags, etc. Kei cars are the smallest vehicles allowed on Japanese highways. You can buy one new in Japan for about $11,000 USD, which honestly seems like a good value. A growing number of Kei cars are being imported to the U.S. under special rules for foreign vehicles that are 25 years old. The most popular models for import seem to be cab-forward trucks with little passenger comfort and even less crash protection, but we can use the winsome N-Box as our point of comparison. The truth is, it would be a viable replacement for something like a Honda Fit subcompact, a hatchback no longer sold in the U.S. which is somehow 25.5 inches longer. My friends who have a Fit might love an N-Box, which would be even easier to park where they live in DC. A new Kei car is a surprisingly compelling package, but returning to our original question, the N-Box weighs about a ton. So it would not solve the physics problem of a car that can ‘more safely’ hit a pedestrian.

And to reiterate, the Fit was discontinued in the U.S., and the N-Box would never be greenlit for sale here, even if it complied with all of our regulations, because the American car buyer would rather pay about twice as much for something new with more space for people and cargo and, by the nature of physics, more safety. Or they could snag a deal on the used market. The Mirage’s biggest competition was used Corollas and Honda Civics, which are better in every way. Before the pandemic, you could buy a CPO subcompact hatchback for about $10,000. Used cars are now heinously expensive, though there are still many new subcompact models for sale in the U.S., mostly crossover “SUVs” pretending not to be hatchbacks, like the Kia Soul.

Designing and, more to the point, marketing subcompacts as SUVs allows automakers to charge more. Small cars also have a thinner profit margin, making the business case even harder as U.S. car buyers turn away from the smallest, cheapest new models.

A major relevant physics problem is fuel or energy efficiency, and aerodynamics. To grossly overgeneralize, one way to make a car more efficient is to elongate its body, so air flows more smoothly along exterior surfaces. Drag increases with the square of speed, so this is especially important for, say, maximizing an EV’s highway range.

In terms of design, the N-Box is a short box stacked on top of another short box. It is only a shade more than 11 feet long! A new Civic hatchback is almost 15 feet long. A new Corolla hatch is about 7 inches shorter than the Civic. The N-Box really is tiny. Despite some rounded edges, the N-Box’s shape and proportions are near optimal for maximizing aerodynamic drag. It punches air in the face then abruptly dumps it off of the back, roiling the atmosphere coming and going. I cannot stress enough how complicated and inscrutable aerodynamics is. Fluid dynamics is an area of physics where theory is still incomplete, and myriad variables mean computer simulations and real-world testing can deliver radically different results. But to oversimplify again, a teardrop is essentially the most aerodynamic shape, and the N-Box is close to the opposite, partially because of its stubby length.

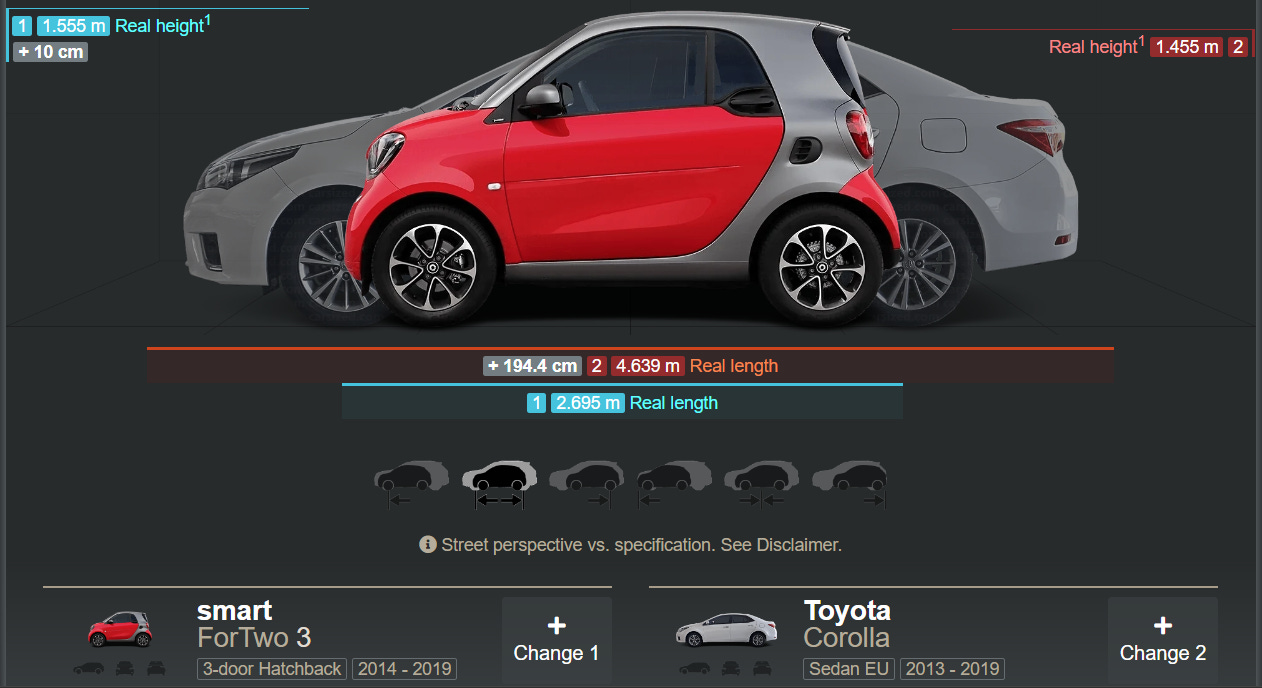

Still, you might be thinking, a Smart ForTwo, the classic Smart car with seating for two and that pretentious name, must be way more fuel-efficient than something like a contemporary Corolla, right? Not really. We can get some hints from carsized.com.

Comparing a hatchback to a sedan is a little unfair, but I want to highlight how much more easily engineers can reduce the drag a car’s body produces if they have more length to work with. Based on the information I could find, the Smart has a much worse drag coefficient (0.38) than the Corolla (0.29), though apparently the prior-gen ForTwo was a bit slipperier. Total drag factor is drag coefficient multiplied by frontal area, and the news from that angle is not great for the Smart car either:

The visuals compare EU-market models but to finish the story we should look at EPA fuel economy ratings of U.S.-spec models, which are more realistic than European ratings. Keep in mind that the Smart has a much smaller engine. The 2017 Smart ForTwo Coupe with an automatic transmission achieves 35 MPG combined, 33 city, 39 highway, on premium gasoline. The 2017 Toyota Corolla sedan with an automatic transmission gets up to up to 32 MPG combined: 28 city, 36 highway. A new 2024 Corolla sedan gets up to 35 MPG combined, 32 city, 41 highway. (The hybrid sedan gets up to 50 MPG combined, 53 city, 46 highway!) So in terms of fuel economy, the contemporary Corolla was not far off from the last Smart city car sold in the U.S. And the push in recent years to maximize fuel efficiency has closed that gap.

One might argue, quite reasonably, that the Smart still has less environmental impact, requiring fewer resources to manufacture, probably throwing off less particulate matter from its tires and brakes, and so on. But any such edge is probably quite modest. To find a practical, attractive car alternative that is significantly smaller than a Corolla or Civic, we will have to look beyond four wheels. What about three?

Once again we find ourselves staring at the Elio, or something like it, an odd but intriguing contraption with two wheels up front, one in the back. It can use many of the same off-the-shelf components as a regular car: wheels and tires, seats, controls, brakes, windshield wiper, lights, engine, etc. The doors could conceivably come off of a regular car, which is a good sign for side-impact protection.

The three-wheeler is arguably much more mechanically similar to a Corolla than the Smart ForTwo, which had a somewhat exotic body structure to offer crash protection comparable to cars with large crumble zones. The three-wheeler can have the same low-drag side profile as a regular car, but its frontal area is obviously much less. It weighs a lot less too. That all adds up to stellar theoretical efficiency. In principle, three wheels are less safe than four, because one rear tire means less rear mechanical grip, and the inherently narrow wheelbase creates rollover risk. But I am willing to accept for the sake of argument that it would be about as safe as a small sedan or hatchback. The crumble zones could be similar to those of a normal car.

So what is not to like? Well, the three-wheeler can carry only two people, one seated in front of the other. And cargo space is at a premium. The three-wheeler is basically a bit more than half of a car. And the wheelbase has to be almost as wide, to provide stability, so it does not end up saving that much space. The empty area extending behind the front wheels is not given back to nature. This vehicle only makes sense as a pure commuter or maybe a car for a childless couple. Target demos beyond that require a lot of imagination. You cannot give more than one co-worker a ride home after work. Unless maybe you are a single parent with only one child, you need something with four seats if you have kids. Most people would rather buy a whole car.

A compact car with decent fuel economy and room for four or five people, especially a hatchback, is an incredibly versatile machine, whether we urbanists want to admit it or not. Yes, car ownership is expensive; yes, cars and driving impose huge negative externalities that appear to be mostly not internalized (costs on other people not borne by drivers); and yes, cars take up vast amounts of space. But outside of metro New York and parts of the DC area and Chicagoland, the U.S. is largely a transit desert. We know that too many people — most people — are truly dependent on driving. So we should keep that in mind and avoid demonizing drivers.

I had a Subaru Impreza five-door and it was great. I helped friends move from one apartment to another. I safely drove in all kinds of conditions. I commuted. I wish the fuel economy were better, but I could have bought a Civic or Corolla. We sold the Impreza when work from home became permanent, and kept our Subaru Forester compact crossover. It was an older design, but it had the room we needed for our young family. Now we have three kids and a Toyota Sienna hybrid that is a living room on wheels and can waft around at 40 MPG under the right circumstances. Especially if you have kids or honestly if you just have places to be, driving is usually most convenient — largely because of unsafe non-car infrastructure.

The most important, attractive alternative to a regular car is not a three-wheeler or a Kei car or an electric car, it is a bicycle, electric or acoustic, and a way to use it safely for daily transportation. Most car trips are a bikeable distance:

This 2022 DOT data shows that more than half of U.S. car trips are five miles or less. And only 6.9% of trips are 31 miles or more! Notoriously few pickup truck owners tow, haul, or drive off-road. How often is an EV driven more than 100 miles in a day?

Especially in a suburban context, where distances can be sizable but roadways are wide and theoretically easy to add bike lanes to, and secure private vehicle storage space is fairly common, I am confident that many people would use a network of cycling infrastructure. My family recently visited the Seattle area: Hilly terrain, wet and dreary weather, and cyclists all over the place. Two key factors seem to be a strong cycling culture and basic investment in cycling infrastructure. Car-lite living is not a fantasy, it is not extreme. You can drive if it rains, I certainly do. Urbanists should be inviting and cheerfully share our tangible vision of convenient alternatives to driving.

Thanks to my 323 subscribers, especially my 9 paid subscribers. If you enjoy this blog or want to work together, especially on my concept for a real estate financing startup, please contact lucagattonicelli@substack.com. I would love to write about a reader-suggested topic. Check out YIMBYs of Northern Virginia, the grassroots pro-housing organization I founded.

P.S. If you liked this post, check out my piece on minivans and automotive safety:

Minivan As Grand Safety Compromise

Next week USA Today should be publishing an op-ed I wrote via Young Voices about why the housing shortage is a literal shortage. And I will be at YIMBYtown early next week in Austin, speaking on a panel about housing advocacy and organizing in the suburbs. Please email

Next generation wiener mobile

I’m curious how the Elio would compare to a three-wheeled motorcycle, with the two wheels in the rear. Obviously there is a safety issue given there are no side panels or roof but how does the drag coefficients compare.