Housing Subsidies Are Moderately Overrated

Reflections on my Newsweek op-ed, plus my new startup

An announcement: I have begun working with a partner to sketch out a real estate finance startup that would enable infill and neighborhood-scale residential development, especially missing middle, and the small and mid-sized developers who create that kind of housing. If you wish to learn more or chat about joining our effort, email lucagattonicelli@substack.com.

Housing subsidies are moderately overrated because many people (mostly normies but likely some housing professionals and advocates as well) view them as an essentially linear tool to make housing affordable: ‘If we spent enough on vouchers or income-restricted committed affordable housing (CAH), we could fix the housing crisis.’

That is not true for two major reasons I outlined in my recent Newsweek op-ed about the limitations of housing subsidies. I have wanted to build out this argument for some time, and am grateful that Young Voices helped me share it with a large, mainstream audience.

A key issue I did not include in the op-ed are long waiting lists for vouchers and committed affordable housing, and the lotteries often used to dole them out. This speaks to the fundamental limitation that these programs cannot scale. Even if we account for higher quantity-demand at below-market prices, there is clearly a huge unmet need, and current subsidy programs are only nibbling around the edges.

So why not just spend more to expand housing subsidies? As I wrote in Newsweek:

Some back-of-the-napkin math can help us put affordable housing in the larger context of the housing crisis. A report from Up For Growth estimated that the D.C. metro region, where I live, had a shortage of 156,597 homes in 2019. That estimate might be low, plus the pandemic made our housing crisis much worse, but I will round down to 150,000.

An optimistic estimate of the typical cost of building one affordable housing unit in the D.C. area is $400,000, though the true cost can be much higher. So addressing only a quarter of the D.C. region's housing shortage with subsidized units would cost roughly $15 billion, comparable to D.C.'s entire $19.8 billion 2024 budget. The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, by far the largest federal affordable housing program, spends about $9.5 billion annually.

Only dramatically expanded or entirely new funding sources would produce that $15 billion for affordable housing in the D.C. region (setting aside the rest of the country). It would be a much tougher political fight than the extremely tense negotiations to fill a $750 million budget gap to sustain our heavily used regional transit system.

And if we secured the $15 billion? Some of it would go toward building 37,500 homes in the D.C. region, reducing the housing shortage. But to the extent the subsidies increased demand for housing, they would also increase prices. Vouchers have the same effect. Landlords would notice that they can charge more.

On the most basic level, a subsidy increases demand. Pouring more money (from any source) into the housing market without fixing the underlying shortage of homes raises prices. Even highly respected left-leaning housing economists highlight that risk.

As the saying goes: more money, more problems.1

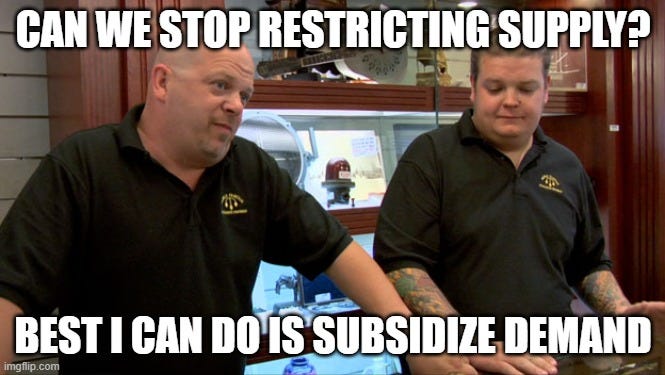

I am anchoring this post to the meme asking, “Why not both?” because my piece is a sincere effort to bridge what is sometimes an either-or debate between demand- and supply-side housing policy approaches. A different news outlet said they would run my op-ed if I rewrote it to squarely criticize subsidies, which I refused to do. My goal was to appeal to folks who support subsidies and question market solutions to the crisis. To be fully honestly, I do see an inherent tension between the two sides of the simmering debate. Increasing demand does, if we believe basic economics, worsen high prices in a supply-constrained market. Quoth another meme:2

However! I do see a case for housing subsidies on merit, even amid our current massive shortage. Especially, not even, because folks with low incomes are essentially shut out of strong labor markets and high-opportunity metro areas. Granting my own skepticism, the nature of unseen opportunity-cost, etc., setting aside political considerations and what I like to call the epistemic modesty of adopting an eclectic policy approach — set all of that aside, and I cannot bring myself to reject these programs, which give a small number of individuals life-changing housing.

Maybe because I am a bit older and have seen more of the world in my own backyard.

My reaction to walking through a community center with an afterschool program for tweens was not “shut it down.” On the contrary, I wondered what, if anything, would fill the vacuum the center would leave. My younger self would here invoke “civil society.” Excuse me, sonny, what civil society? The one that has frayed into almost nothing for a century? I do suspect civic associations, the kind that fed the poor and found people jobs and helped new immigrants adjust to life in America, would do a good job meeting the needs of the least among us, with a human touch that eludes government. Rebuilding such social fabric is a defining challenge of our time.

With that said, housing subsidies are still not a scalable solution. This is an emotional topic that easily devolves into accusations of not caring about low-income people or worse. But especially when discussing how to help our least fortunate neighbors, we have a special responsibility to try to get to the truth, to go beyond good intentions. We must strive for a strategy that works, that actually helps people.

I worry that affordable housing programs allow elected officials to claim that they are “taking action” and “investing” and “tackling the problem,” perhaps adding that, “We know more needs to be done.” Few if any politicians would pose for the ribbon-cutting in front of a large market-rate apartment building (it might be shortest shortcut to being voted out). In Northern Virginia, subsidized affordable housing is, on balance, politically popular. As far as I know, CAH is decidedly unpopular in the more conservative sunbelt, for example, and perhaps most of the U.S. So my political expediency concern only goes so far. However, I also worry that housing advocates put themselves in a box by viewing subsidies as integral to what will have to be a much larger strategy to fill the vast housing shortage.

To scrutinize myself, I will now introduce thoughtful critiques of my op-ed from my chum

, an affordable housing pro who blogs about the brass tacks of development and real estate finance. His comments are minimally edited for clarity:Your overall point is a good one, but a few follow on thoughts:

1) For markets with adequate supply, demand-side subsidies (e.g., housing vouchers) to poor people are some of the most cost-effective means of delivering needed assistance. This is especially true in the short-term. Here’s an article interesting link: https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/more-housing-vouchers-most-important-step-to-help-more-people-afford-stable-homes

The caveat “with adequate supply” is critical, as Brian and I agree that the current shortage is overwhelmingly large. I assert in the op-ed, based on fairly clear evidence, that housing subsidies help millions of people in the U.S. avoid homelessness. A corollary to Brian’s first point: He may have been the person who explained to me that most homelessness is short-term, with a lot of churn in the overall homeless population. Most folks without stable housing at a given time find it fairly quickly. The homelessness we usually see and talk about, individuals chronically sleeping outside or maybe in a shelter, is a minority, albeit a no less important one.

2) For people at or below the poverty line, there’s almost no supply side solution (market or subsidized construction) that would make housing affordable for them. Below a certain income level, there’s no way to operate a building at rents that are low enough to be affordable for this group (excluding group homes, etc.). So vouchers are critical for this very vulnerable group, especially since a lot of people in this group live on a fixed income and are not in the workforce.

Brian is an affordable housing developer, so I am inclined to accept his analysis of real estate cost structure. I have seen Jenny Schuetz, a world-class housing economist and Brookings scholar, make the same basic claim about residential buildings’ baseline operating expenses exceeding the rent that the lowest-income tenants could pay.

I close the op-ed by arguing that narrowing the housing shortage can make subsidies more effective, noting first that reducing market prices will allow each dollar spent on vouchers, for example, to go further, ultimately serving more people in need. This speaks to the population in Brian’s second point. His final one:

3) Most LIHTC renters are not at poverty line, but somewhere above it, so they don’t fall into the category of #1 and #2 above. They’re more likely people with low-income jobs (e.g., cab drivers, health care assistants, etc.) for whom the market doesn’t produce affordable housing. Although we [his employer, a nonprofit developer of affordable housing] do have a small number of people [tenants] at or below the poverty line, who willingly pay a lot more than they can afford at LIHTC rents so that they can live in Arlington closer to their job or where there are good schools.

I’m sure you know a lot of this already.

Brian is characteristically generous. Yet this may be where we disagree. His third point seems to refer to what is traditionally called “the working class.” I have a hard time accepting that the housing market is structurally incapable of serving that population, which I think of as including first responders and teachers. When I met my wife in early 2016 she was a public school teacher who spent half of her income on a monthly rent of $1,200 — low even at the time for a big one-bedroom, for our area. Is $1,000 or $800 rent for a comparable apartment so far out of reach? We cannot feasibly build our way to that level of abundance? Even granting that my better half’s garden apartment was built in 1925 and decades out of date?

I close my op-ed with the hope that…

we will be able to spend less on "workforce housing" programs that benefit households making between 60 percent and 120 percent of local median income. Folks who make that much money should expect to afford housing without a subsidy. We must allow the market to build the homes that will allow teachers and first responders to live in the communities they serve.

As of 2023, only 13 Alexandria City firefighters, serving a population of more than 150,000, lived within city limits. Some were recruited from Pennsylvania. Many live there, making the long drive every few days. Surely the market can do better.

Click here to read my entire Newsweek op-ed on housing subsidies.

Thanks to my 288 subscribers, especially my 7 paid subscribers. If you enjoy this blog or want to work together, please contact lucagattonicelli@substack.com. I would love to write about a topic suggested by a reader. Visit YIMBYs of Northern Virginia, the all-volunteer grassroots pro-housing organization I founded, at yimbysofnova.org.

I am more of a Tupac fan but am glad I got to invoke Biggie in a national op-ed, not to mention linking to Cardi B cursing NYC’s acute shortage of housing inventory.

Demand changes have already had a huge effect on the macro level. My friend Salim Furth (Salim’s Substack), a Mercatus housing economist, pointed out in a recent podcast appearance that the COVID-19 housing shock was a demand shock. People decamped from California and elite coastal cities (and Denver?) for more living space and lower cost of living, helping bid up housing in essentially all areas of our country with jobs.

Salim notes that no housing market could realistically absorb such an extreme short-term shock, because it physically takes a few years to build housing. But of course, the shock has exposed the dire extent to which overregulation prevents supply from expanding to meet demand. Not that Salim was suggesting otherwise, but I would argue that COVID accelerated a long-term trajectory that we would still be struggling to escape. In other words, we cannot credibly blame the pandemic for the national housing crisis.

![Request] "¿Por qué no los dos?" Taco Girl : r/Makemeagif Request] "¿Por qué no los dos?" Taco Girl : r/Makemeagif](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!WHWx!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F891b3a6c-06fe-4669-890d-28d9f84cd8d5_465x349.gif)

Good stuff, and thoughtful as always. Very interested to learn more about your new project!