The Two Paths To Inexpensive Housing

Abundant supply is possible, and preferable to low quality

Do you think abundance is a viable strategy to make housing inexpensive? My family’s recent visit to the Seattle area pushed that question to the front of my mind.

My friend

has a new piece sharing his disappointment with Seattle, particularly the horrific spectacle of individuals living on the street, many tormented by hard drug use and festering medical conditions. These are human beings and Addison is careful to humanize them and recognize their inherent dignity. He also notes that he has not seen such mass homelessness and suffering in DC or New York City, which seem to have recovered better from the pandemic.My wife and I drove our three young kids to and from Seattle’s Pike Place Market, never seeing the nearby blocks that have become skid rows. She did say, based on her own observations and her parents’ experience living in the area, that Seattle has gotten rougher in the past eight years. Redmond’s Target has had to lock away items due to organized retail theft. Happily, I never felt unsafe during our visit. I met someone for lunch near Nordstrom’s flagship store with a security guard out front, then walked around a little afterward. The area was fine, the architecture was above average! My lunch companion explained that the true “business downtown” with few residents has fared far worse, setting up conflict between the much reduced population of office workers and people living on the street or just milling around.

Though I did see many clusters of tents in Seattle proper while driving in the city, to me the deeper sign of dysfunction was ubiquitous graffiti. Some was political, with a message that doubling down on dysfunction is the only recourse of the oppressed in a capitalist system. Obviously my diagnosis is different. I saw “kill pigs” spraypainted on a sign at a park in the pleasant Green Lake streetcar suburb neighborhood, yet was somehow more surprised and disappointed to find “revolution is coming” tagged on a nearby children’s wading pool — extravagantly self-indulgent and out of place. Disregard for children’s innocence really rubs me the wrong way.

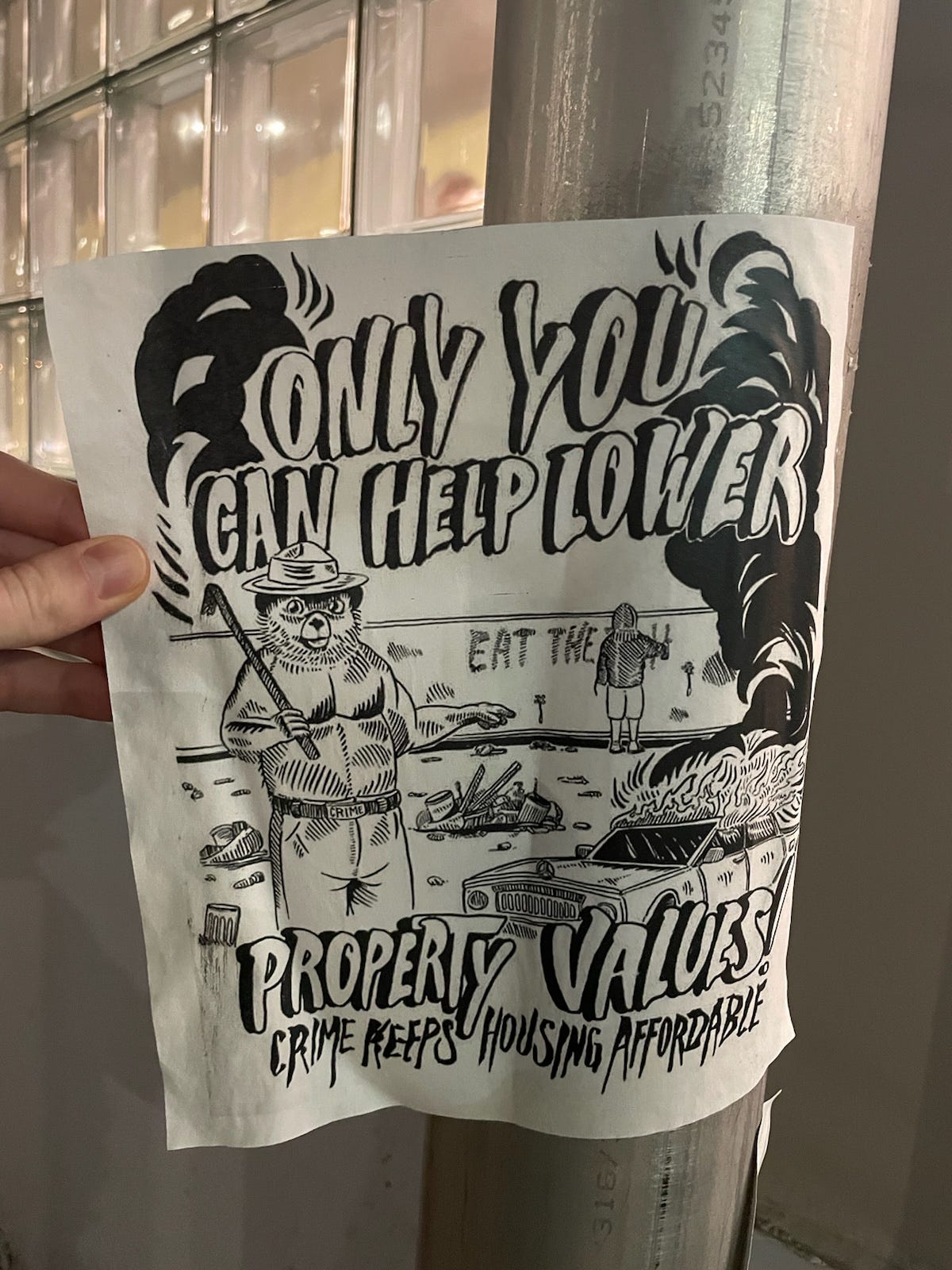

Another Seattle YIMBY friend shared the most overt example of urban cynicism, the top photo. “Crime keeps housing affordable.” How much does the person who wrote that have to worry about being a victim of crime, I wonder. That all leads back to my original question: Do you think abundance is a viable strategy to make housing inexpensive? How confident are you that a reasonably unencumbered market could deliver enough homes to make housing affordable to anyone with a decent income?

As I have argued at length, subsidies cannot meaningfully scale, politically or economically. So the only other realistic path to inexpensive housing is low-quality housing. I refuse to accept that option for other people. Yet it gets a lot of credence.

Note: You might object that I am neglecting social housing — public development and management of housing. I have deep seated skepticism, in general and given inefficient American bureaucracy and public administration. Public housing is also not a mainstream idea in the U.S. — not fringe, but not within the Overton window in most regions. And it has a troubled history, which I need to learn more about. So I am setting it aside in this discussion. Strictly speaking, I do not think public housing is a viable path to inexpensive housing. Some YIMBYs do, which is fine. I freely admit that they know a lot more about it than I do.

“Naturally occurring affordable housing” is typically run down garden apartments occupied by working-class families in an expensive metro area. Garden apartments are low-rise structures, usually no more than three or four stories, characterized by lots with considerable open space and greenery and trees. My wife and I lived in such a building in Alexandria’s Del Ray neighborhood, which I regularly invoke. Monthly rent was $1,200 about eight years ago, cheap for a one-bedroom, especially of that size and near Metrorail in such a desirable neighborhood. But it had hallmark problems of an outdated building: Radiators that stayed on after the weather had warmed up, thin walls, and a fuse that would blow if the microwave and toaster oven ran in concert.

Garden apartments are easy to romanticize (especially as a rationale to block denser housing). The garden imagery is a textbook case of folks mistaking pastoralism — proximity to greenery — for environmentalism, which is using resources efficiently, reducing pollution, and actually limiting ecological damage such as new exurban sprawl. At least in Northern Virginia and DC, many garden apartments are ripe for redevelopment to a more intense land use, such as mid- or high-rises. Del Ray NIMBYs live in fear that one day the garden apartments I lived in — note well, near Metrorail! — will be redeveloped into larger apartment buildings. That economic tension raises the specter of displacing current residents of old garden apartments. Purchasing and “preserving” such housing is a respected regional housing strategy.

Since I mention displacement, my understanding is that empirical studies find that new market-rate housing has a positive or close to neutral effect on whether residents in the immediate vicinity can stay in their homes, and a robust positive effect at the regional level on housing affordability. You might be able to persuade me that new development will displace low-income families in the short term. Nevertheless, that population will ultimately suffer the most if their region builds no new housing.

As in my discussion of housing subsidies, I cannot fault someone who has these concerns and sees preserving “naturally occurring affordable housing” as a necessity. There are people suffering now who — I and presumably most people would agree — deserve help now. Yes, and: the stakes of these discussions are so high because the people living in cheap, low-quality housing have such meager alternatives.

The full implications are probably obvious to you, dear reader. Housing reform supporters of almost all stripes, including affordable housing advocates — in non-profits, in government, in academia and think tanks — will regularly acknowledge that supply is an underlying problem, the subtext being that ‘someone should do something about it.’ The YIMBY movement is so important because we are. We uniquely target the root cause of the housing crisis. Let that sink in for a moment. I know not to say that as a fundraiser to a community foundation, we should always emphasize our partnerships and the coalitions we build. Still, our role is unique.

Do not be discouraged by pushback from “neighborhood defenders” (do not get me started) or fellow advocates. We take the most NIMBY flack because we fly directly over the target. This is why the YIMBY movement must professionalize. This is why I intend to start a company that helps finance missing middle housing and the small developers who create it. Affordable housing always makes me think, “We need a bigger boat.” Building that boat is the essence of YIMBY. No one else will do it for us.

Thanks to my 332 subscribers, especially my 9 paid subscribers. If you enjoy this blog or want to work together, especially on my concept for a real estate financing platform, please contact lucagattonicelli@substack.com. I would love to write about a reader-suggested topic. Check out YIMBYs of Northern Virginia, the grassroots pro-housing organization I founded.