What I Miss About the Deep South

Something surprising, if you have never lived there

Part of this blog’s mandate is exploring the world we build for each other. That includes segregation, which is largely a product of housing policy, but also of culture. For those concerned about my topical waywardness, please know that my next piece will be about urban street design.

I grew up in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, across the majestic Cooper River from Charleston, the epicenter of the American slave trade and wealthiest city in the thirteen colonies. About 40% of African slaves entering North America came through Charleston. The city’s wealth enabled the founding in 1770 of our nation’s first municipal college, the College of Charleston, where I attended the honors college. Three of my alma mater’s founders signed the Declaration of Independence. Three others signed the Constitution. Their families — Middleton, Pickney, Rutledge — owned large plantations. Old Southern money is blood money.

After graduating in 2012 I moved to DC, then Northern Virginia. I was struck by an unfamiliar, unsettling feeling of separation from black people, namely the descendants of African slaves. One of the first black people I interacted with in the area was a teenage cashier at a McDonalds in DC. We did not make eye contact. He clearly saw was no reason to. We lived in two completely separate worlds.

I am sharing my experiences because they contradict how many Americans, especially a certain set of white individuals, talk about the South, race, and what used to be called race relations. A liberal friend who works at a nonprofit says this sort of essay is a well-established genre, at least among liberals who work at nonprofits. A truism among Black advocates is: “In the North, they don’t care how high you get as long as you don’t get too close; in the South, they don’t care about how close you get as long as you don’t get too high.” Before I go any further, disclaimers:

I want to avoid sweeping generalizations. I only claim to be sharing my own perspective, which is surely skewed and incomplete. It is an outsider’s perspective.

The South Carolina Lowcountry was objectively not the best place for me to grow up. It was a poor cultural fit. My father is an intellectual and research scientist who originally immigrated from Italy. Lowcountry denizens have perfected the art of savoring the good life and not thinking too hard. Sweet tea was invented there. Conformity is prized. My mother is a Bostonian WASP, the cultural opposite of the Deep South. She remembers being regularly honked at when we moved down, until she learned to drive less aggressively. Upon moving to the DC area I immediately liked the faster, though not breakneck, pace of life and that it felt culturally placeless, a cosmopolitan mesh of newcomers.

Another caveat is that I simply do not think the way most people think — not better or worse, just differently. I was a terrifically awkward and socially graceless well into my 20s, with near-zero friends as a kid. I actually got along better with my black classmates in some ways. They tended to be unpretentious and open-minded. I felt so different from almost every peer, while our racial differences felt inconsequential.

Yet I think my classmates felt roughly the same way about race. I attended racially integrated public schools. The white and black kids often kept to themselves, sure, especially at lunchtime, but friendship networks casually spanned that divide. In high school there was the white girl who always hung out with the black kids. A few black kids always hung out with a white crowd. I somehow took a beautiful black girl to junior prom — me, the hapless weirdo who was medically incapable of shutting up. That says more about my high school’s social dynamic than it does about me. My having a prom date is proof God performs miracles. Her being black was a nonevent.

Part of my frustration is how some white people who grew up in places like Connecticut casually, or haughtily, assert that the South is the beating heart of racism in America today. Around 2019 I heard a colleague say, ‘Of course everyone in the South is racist.’ I had to politely explain to my chum that, if anything, anti-black racism is a social taboo in the South more so than any other region, because Southerners had to confront Jim Crow and figure out some way to move forward.

And to be fully candid, white people lecturing other white people about “making room for people of color” feels completely foreign to me and increasingly unhelpful. These conversations, to characterize them charitably, pointedly leave no room for curiosity about personal experiences, backgrounds, or values. If I want to relate to a black person or, you know, just a person, pretty much the worst thing I could do is (1) think like an academic and (2) carefully script myself in a way that is perceptibly more mannered and fundamentally different from how I normally communicate. It risks giving the person the impression that I think them to be less than capable. Code switching is fine, but do not overthink yourself into acting like an anthropologist.

Obviously I asked my parents questions about things like the KKK, but we did not talk much about black people because we lived with them. That is what I miss.

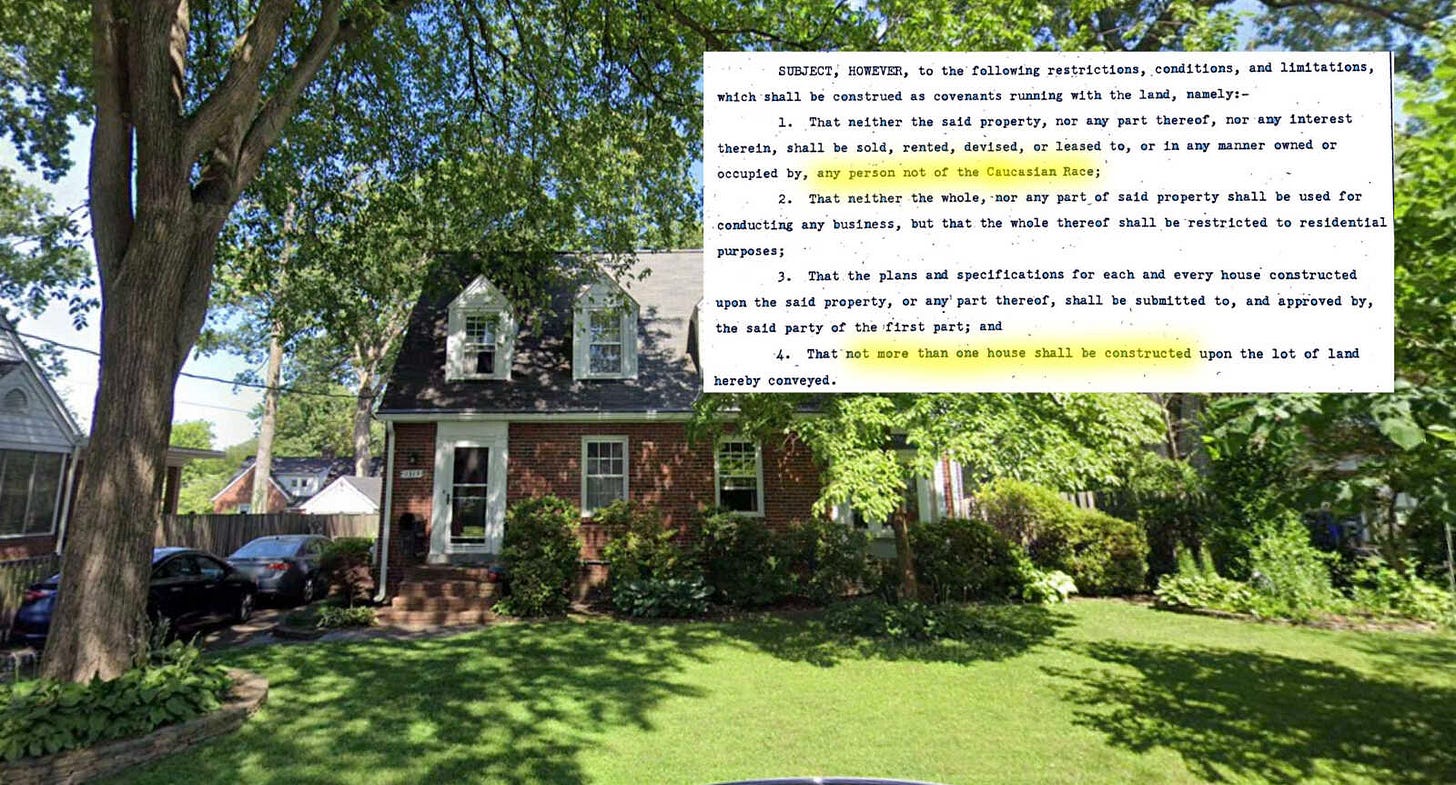

The rest of the country relishes looking down on the South because of its racist history, from slavery to segregation. In this regard, Northern Virginia remains decidedly Southern. A restrictive covenant used to block a duplex in Arlington also barred non-white people from buying or renting. Racist legal instruments retain the power to make a developer give up on a duplex and build a mansion instead.

(The Arlington NIMBY who urged her neighbors to weaponize deeds that just so happen to contain white supremacist language appears to be the FBI’s chief marketing officer. I abhor cancel culture … but … )

Opponents of Arlington’s missing middle housing reform invoked an early-1960s political bargain to concentrate residential density around Metrorail stations and “preserve” single-family neighborhoods. That compromise predated the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1968 Fair Housing Act. The county’s black population was at a historical low: 5% in 1950 and 1960, 6% in 1970, compared with 38% in 1900.1 Some reform opponents would even say, ‘I know these zoning laws were created with racist intent, but we should not change them now.’ As for South Carolina, the Federal judiciary ordered its schools to fully integrate in 1970. Legal segregation can barely be called history. I got a stark reminder one morning in my college’s cafeteria.

There I sat blearily near the omelet station. The station had a system: you put the ingredients you wanted in your omelet in a little bowl and handed it to the black woman behind the counter, who would make the omelet. It was almost always a black woman, or maybe a black man. Nowhere am I claiming the South is a racial utopia. Up sauntered three or so white men around the same age as the woman behind the counter, probably in their 50s. The leader of the pack swaggered to the counter and said with a smirk, ‘I want you make me a bacon, egg, and cheese.’

And the black woman grinned right back at the white man and said, ‘Well you can just make it yourself.’ You could have cut the tension with a knife. If these individuals were in their 50s around 2010, they would have been children around 1970. They may well have attended segregated schools. That moment is objectively one of the coolest things I have ever witnessed. I will never forget it. I still remember her face.

Yet I would not call her act exceptional, in an important sense. The black people I grew up with were not fragile. My black teachers and classmates had dignity and they expected to be treated with respect. They did not want to be condescended to. No one does. I grew up with a cultural and social expectation that everyone was entitled to respect, the right to look each other in the eye.

Yet somehow it was in DC, even in the halls of Congress when I was a reporter, where I found that many older black men would keep their gaze down, not meeting mine, if we walked past each other. If I greeted them their only reply would be, “All right.”

The white Southerners I grew up with were clearly determined to defy regional stereotypes and move forward. They were, as far as I could tell, profoundly ashamed of slavery and segregation and older black men not looking white women in the eye for fear of being lynched. I absolutely did learn about my state’s putrid history of racism, especially in middle school. I visited the Old Slave Mart Museum in Charleston around the age of 21. I discovered that I was already past my prime; my value at auction peaked when I was 19. I saw the iron shackles that went around slaves’ wrists and ankles and necks. The only thing I can personally compare it to was seeing a bar of soap made from human fat, in a museum of Nazi atrocities in Krakow. The history of slavery is something the rest of the country reads about. I grew up immersed in it.

In Charleston I regularly walked past a plaque marking the site of the building where the first Ordinance of Secession was signed. We went on field trips to plantations, visiting mansions like Drayton Hall. The Lowcountry is a beautiful place built on the ugliest possible foundation.

Yes, of course, all of this is complicated and context-dependent. Yes, of course, my black classmates had frustrations about racial dynamics and double standards and being followed around by store clerks. I am not speaking for anyone else, I am just telling you what I have perceived. Obviously there are pockets of white good old boys and Southern blue bloods who still think about the property they lost in “The War.”

However, I am saying that daily life in the South of my childhood and adolescence was racially integrated in ways that New England’s social justice warriors only dream of. Black people were not a curio, they were just between a third and two-thirds of the people I would see at a given store. As a teenager I saw more and more multiracial couples. And remember, I grew up in a middle class suburb. Mount Pleasant had a small black population (~3%), but a third of Charleston County residents were black.

So Arlington’s small black population, about 10% since 1980, does not seem to be the biggest reason the county and the region feel segregated, so much more than the Lowcountry did. The black parts of DC are only a short Metro ride away.

Usually I offer solutions in my writing and try to be positive. I mean no offense. This feels worth sharing partially because it is uncomfortable. Our conversations about race are too simple, too clean. The South is often pushed into the role of scapegoat. As a poet once said, the South got something to say.

Thanks to my 744 subscribers, especially my 11 paid subscribers. If you enjoy this blog or want to work together please contact lucagattonicelli@substack.com. Check out YIMBYs of Northern Virginia, the grassroots pro-housing organization I founded.

Highland Park Captured My Heart

On a recent road trip, we stopped in Pittsburgh to catch up with my best friend from childhood over lunch at a family-friendly bistro. Highland Park is a streetcar suburb about 15 minutes from downtown by car. I was blown away by its rich fabric of closely spaced homes with porc…

Data compiled by D. Taylor Reich.

Great piece. I’m a working class kid from the south and integration is just a given. We were all down there at the bottom together. Having lived long enough to become, for a time, a professional class liberal in the north, there’s just a lot less hanging out comfortably with people of other races in that milieu. To the extent that it happens, it’s mostly not with black people.

I actually think the liberal race obsession makes hanging out with black people, in particular, more fraught. Having to worry about stepping on various mines, things like “cultural appropriation”, makes it less likely that people of different races will simply chill together. For people who take it to heart; people in the south who ignore that stuff are mostly doing what they’ve always done. But I have found the introduction of all speech and behavior coded, obsessions with privilege and power dynamics, sort of heartbreaking. It isn’t progress, not at all.

I relate to this to a degree. I went to high school in a very diverse Texas suburb. Racial tension was not really a thing, the neighborhoods were quite mixed and there was no large majority group so the salience of race was just not very high.

As an adult I lived and worked in the very segregated city of San Francisco and routinely listened to people make scornful pronouncements about those horrible racists in Texas and how everyone there lives. A few times I described my parents neighborhood and my school, and people didn’t believe me. “You must have been in a really unusual situation.” But, no, I wasn’t.

For certain people this is part of their social status. They learned in history class all about *those states.* They can look down on those states and their people. Actually, it’s a bit like… well, nevermind.