YIMBY For Conservatives | The "Me" Generation

Double feature: National Review op-ed + examining bibliographic evidence

I was a neoconservative two or three ideological transformations ago because I grew up reading National Review.1 So it was a cool full circle moment seeing my piece about the conservative case for YIMBY published on the front page of NR’s website this past Sunday, the end of my stint with Young Voices.

I chose the topic after hearing a rumor that some conservative donors wanted to foment an anti-YIMBY backlash. The piece is paywalled but I feel within my rights sharing these key excerpts:

The truth is, YIMBY is not partisan, and urbanism does not require any notable ideological commitments. However, the YIMBY policy agenda boils down to deregulation. And our vision for neighborhoods with tight communities, abundant starter homes, and thriving young families is arguably small-c conservative, a return to traditional American land use.

My top priority was making a pitch against minimum lot sizes and for starter homes:

The zoning restriction conservatives should object to most is minimum lot sizes, which make starter homes financially infeasible. Land is expensive, so large lots incentivize larger, more profitable houses. Minimum lot sizes proliferated after 1940 to exclude young families who might cost public schools more than they would pay in property taxes. The regulation may also have been aimed at black Americans migrating north. It still harms young families and low-income Americans, anathema to the conservative ethos of opportunity and upward mobility.

Conservatives should also be leading the charge against often Kafkaesque permitting. My city’s permitting office performed some kind of archeological review before I could remodel my townhouse’s third-floor bathroom. More troublingly, I watched a family politely beg my city council for a zoning variance so they could stop sewage from regularly flooding their basement.

I closed by emphasizing that YIMBYs tend to be middle-class, pro-family nerds:

YIMBY movement pioneer Sonja Trauss stresses the importance of street trees. YIMBYs’ favorite neighborhoods are streetcar suburbs built a century or more ago. We overanalyze street cross sections, dreaming of the day that America’s kids can safely play and bike in front of their houses. And we commiserate about hoping to buy a home or start a family.

The YIMBY movement is an attempt to rebuild the American dream of a comfortable middle-class existence with a stable family life and good friends. I could call that aspiration many things, yet the first term that comes to my mind is conservative.

I am not a conservative and, like most of my conservative friends, could never vote for Donald Trump. Yet bringing people of goodwill from all kinds of backgrounds into the YIMBY movement will continue to make it stronger. I previously wrote about post-YIMBYtown tension, which centered on YIMBY’s embrace of conservatives.

Conservatives might appreciate this too, which is the smoothest transition I can offer.

Being neck-deep in two local zoning reform campaigns exposed me to many angry baby boomers arguing against density and growth out of naked self-interest, a fear of change (rather than reduced property values) that shone through all attempts to dress it up. Reflecting on their testimony, I am struck by how righteously personal it was. Personal injustice seemed to be the moral foundation of their entire perspective.

I should note that despite obvious tensions between my (millennial) generation and theirs, I do not mean to attack baby boomers. Some of the finest people I know are baby boomers! Including my parents and one or two members of my YIMBY group’s leadership team. I have advocated for housing alongside individuals of all generations.

Yet NIMBYism as I know it is difficult to extricate from a baby boomer sensibility. David Brooks of all people offered some perspective that seems useful. With the caveat that he left his wife for his much younger research assistant, Brooks has written two long essays on relationships and ties that bind which have heavily influenced me. The first is the cryptically titled, “The Nuclear Family Was A Mistake,” which argues that self-contained parent-child households are ahistorical and set up families for isolation, in the face of an overwhelming stream of domestic labor. Brooks argues for a return to kin relationships and intimate community.

The second is, “How America Got Mean,” an even more uselessly titled examination of the lost art of what Brooks calls “moral formation” in American education.

The most important story about why Americans have become sad and alienated and rude, I believe, is also the simplest: We inhabit a society in which people are no longer trained in how to treat others with kindness and consideration. Our society has become one in which people feel licensed to give their selfishness free rein. The story I’m going to tell is about morals.

Moral formation, as I will use that stuffy-sounding term here, comprises three things. First, helping people learn to restrain their selfishness. How do we keep our evolutionarily conferred egotism under control? Second, teaching basic social and ethical skills. How do you welcome a neighbor into your community? How do you disagree with someone constructively? And third, helping people find a purpose in life. Morally formative institutions hold up a set of ideals. They provide practical pathways toward a meaningful existence: Here’s how you can dedicate your life to serving the poor, or protecting the nation, or loving your neighbor

Then he chronicles historical examples such as UChicago’s great books program.

These various approaches to moral formation shared two premises. The first was that training the heart and body is more important than training the reasoning brain. Some moral skills can be taught the way academic subjects are imparted, through books and lectures. But we learn most virtues the way we learn crafts, through the repetition of many small habits and practices, all within a coherent moral culture—a community of common values, whose members aspire to earn one another’s respect.

The other guiding premise was that concepts like justice and right and wrong are not matters of personal taste: An objective moral order exists, and human beings are creatures who habitually sin against that order. This recognition was central, for example, to the way the civil-rights movement in the 1950s and early 1960s thought about character formation.

Finally he reaches the mid-20th century pivot to a self-centered personal ethic.

A culture invested in shaping character helped make people resilient by giving them ideals to cling to when times got hard. In some ways, the old approach to moral formation was, at least theoretically, egalitarian: If your status in the community was based on character and reputation, then a farmer could earn dignity as readily as a banker. This ethos came down hard on self-centeredness and narcissistic display. It offered practical guidance on how to be a good neighbor, a good friend.

And then it mostly went away.

The crucial pivot happened just after World War II, as people wrestled with the horrors of the 20th century. One group, personified by the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, argued that recent events had exposed the prevalence of human depravity and the dangers, in particular, of tribalism, nationalism, and collective pride. This group wanted to double down on moral formation, with a greater emphasis on humility.

Another group, personified by Carl Rogers, a founder of humanistic psychology, focused on the problem of authority. The trouble with the 20th century, the members of this group argued, was that the existence of rigid power hierarchies led to oppression in many spheres of life. We need to liberate individuals from these authority structures, many contended. People are naturally good and can be trusted to do their own self-actualization.

Niebuhr is a compelling figure, but the rub is that Rogers and company’s focus on self-actualization created not only a rationale but also a sincere imperative for people to endlessly turn inward. The good life became a highly personal quest centered on identity and, I would argue, introspection and reflection rather than productive action, not to mention fellowship. Many of us grew up with a basic message that we should try to think our way out of problems, especially personal struggles.

Despite the best of intensions, this self-centered way of going through life is inherently narcissistic, which brings us to the “Me” generation, a term for baby boomers that emerged in the 1970s as they became professionals and consumers.

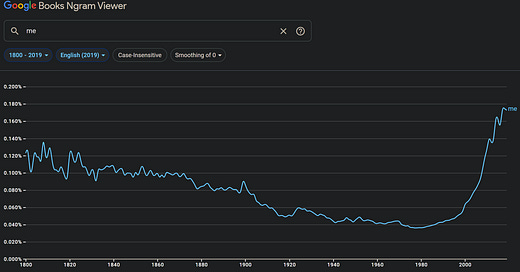

Before considering Google’s Ngram book data, I wish to suggest that social trends and cultural shifts happen on a margin. There are all kinds of behavior in the world at any given time in history, ranging widely from the depraved to the sublime. This might be only circumstantial evidence, and hopefully I would have the intellectual integrity to report whatever I found. But the data were striking beyond my expectations.

After peaking in 1899, mentions of “me” in books steadily fell off until around 1980, beginning an exponential increase through 2019, the final year of data. We see a similar pattern for mentions of “I” in books. Pew defines baby boomers as born between 1946 and 1964. In 1980 that cohort was between 16 and 34 years old. And as best I can tell, authors generally publish their first book in their 30s or 40s. So it appears baby boomers did trigger a flood of “I” and “me” in the literary canon.

Perhaps fiction has simply become more common. Yet even if authors were using “I” and “me” to quote or refer to other people, the implication of social and cultural self-preoccupation seems almost undeniable. Make of that what you will.

Happy Independence Day to my American readers. When I listen to this piece, I cannot help but feel optimistic about our country’s future, in spite of everything.

Thanks to my 424 subscribers, especially my 12 paid subscribers. If you enjoy this blog or want to work together, especially on my concept for a real estate financing platform, please contact lucagattonicelli@substack.com. Check out YIMBYs of Northern Virginia, the grassroots pro-housing organization I founded.

I read a serious proposal in NR to assassinate Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, before the U.S. government normalized relations with conservatives’ approval, before it then turned on him again for cracking down on the Libyan people during the Arab Spring.

As a former conservative turned never-trumper turned I don’t even know what, I really appreciated this article.

I’m not sure that I’m ready to become a full-blown YIMBY, but affordable housing is probably the most important issue facing Americans today. And the YIMBY’s appear to be the only group interested in providing real solutions.

Keep up the good work

I'm a conservative, Kamala Harris voter in Arlington, VA and I support Luca